| ||

Harold Holt in the 1930s |

| |

Walter, who was also called Igo, in happier pre-war days with his father Dr Johan Glaser (centre). |

|

Jews in Vienna forced to scrub Schuschnigg's slogans off the sidewalk as Nazi soldiers watch |

|

Walter Glaser as a child. His family nickname was "Igo". |

|

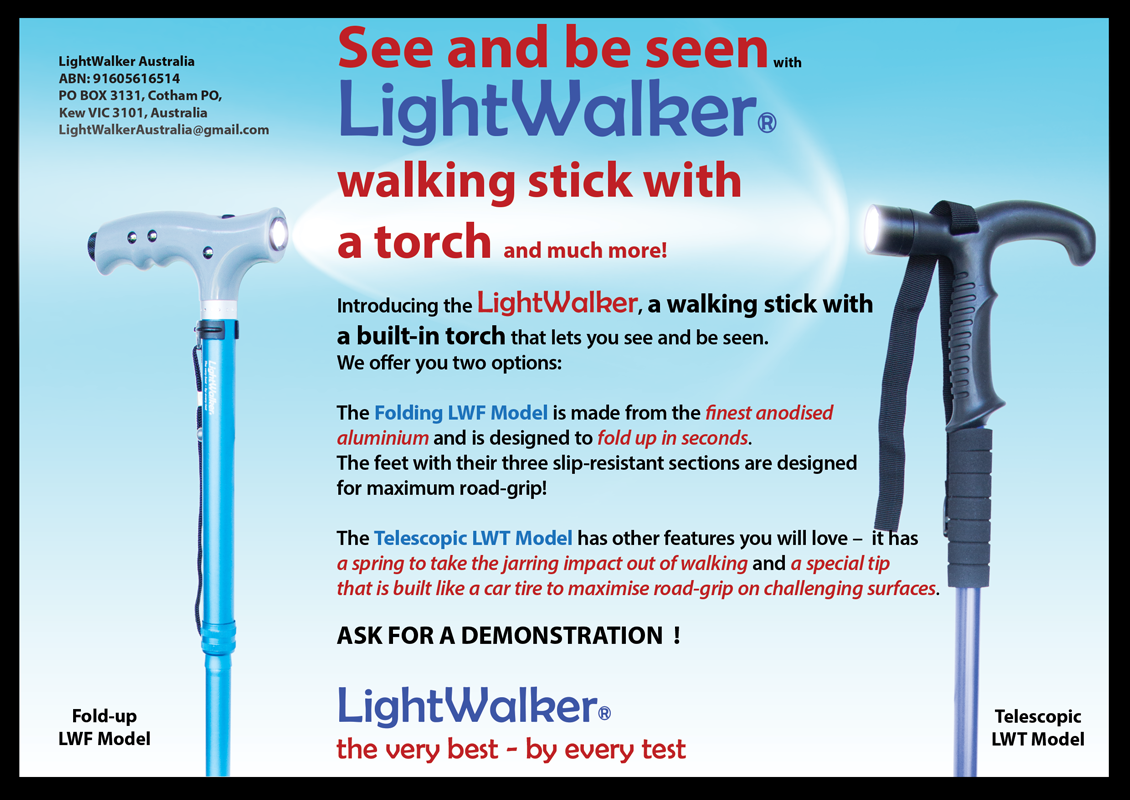

The Glaser family arrived in Australia on the SS Nieuw Zeeland |

|

Walter Glaser, (then) 87, says "if we had stayed, there is no question that we would have been wiped out. We would have been killed. "We came out in style but arrived with nothing," he says of the journey to Melbourne. "My father was no longer a banker."

Like a lot of Jewish refugees to Australia at that time, Walter's father started a business in the garment industry – producing clothing labels.

Walter encountered his first experience of anti-Semitism at Elwood Central School in 1938. "I arrived at Elwood Central School wearing lederhosen and got bashed up in the morning for being a kraut and bashed up in the afternoon for being a Jew," he says.

Dr Glaser died in 1946 aged 49 from rheumatic fever. Walter, 16 years old at the time, took over running the family business. Six years later, while studying at night school, Walter was offered admission to the MBA program at Harvard. He declined because he knew his mother could not run the business by herself. "My dad died when I was 16 and I had to get stuck straight into the business. I went back to university in my 40s," he says.

Walter went on to have careers in advertising and travel writing, before gaining further qualifications in psychotherapy and economics. In 2012, head of collections and curator at the Jewish Holocaust Centre Jayne Josem interviewed Walter about the impact of "this random act of kindness" by the dinner party guests all those years ago.

He replied: "If something good happens to you, you are duty bound to pass it on to others."

He and his wife, Cherie, were in Istanbul in the late 1980s when upheaval in then-communist Eastern Europe was widespread and they befriended a young Romanian shop assistant. The shop assistant had been an officer on a Romanian vessel who jumped ship in Istanbul because as a Catholic he was being persecuted and bullied. He was working and waiting in Turkey for migration to a western European country.

The Glasers upon returning to Australia began trying to sponsor his entry into Australia. They sent him money every month. When eventually he was granted entry to Canada they helped him financially to settle there. And when the communist leader of Romania, Nicolae Ceausescu, was executed they sent him $2000 "to fly back to your homeland and pick up your wife and children fast", Walter said..

"I feel that this is just part and parcel of repeating the cycle of helping," said Walter. "When you have been so incredibly fortunate [as my family was] you are beholden to help others to do the same thing."

Walter Glaser was a past member of The Rotary Club of Moorabbin |

|